High-pressure processing (HPP) is a food pasteurization method where food is subjected to elevated pressures (up to 87,000 pounds per square inch, or 6,000 atmospheres, or 600 MPa), at ambient or chilled temperatures, to alter the food’s attributes to achieve consumer-desired qualities. HPP also inactivates harmful and spoilage microorganisms, facilitates food safety, and extends food shelf life while retaining food quality and maintaining natural freshness. Since pressure treatment at ambient or chilled temperatures does not inactivate bacterial spores, treated products are typically distributed under a refrigerated environment. The process is also known as high hydrostatic pressure processing (HHP) and ultra-high-pressure processing (UHP).

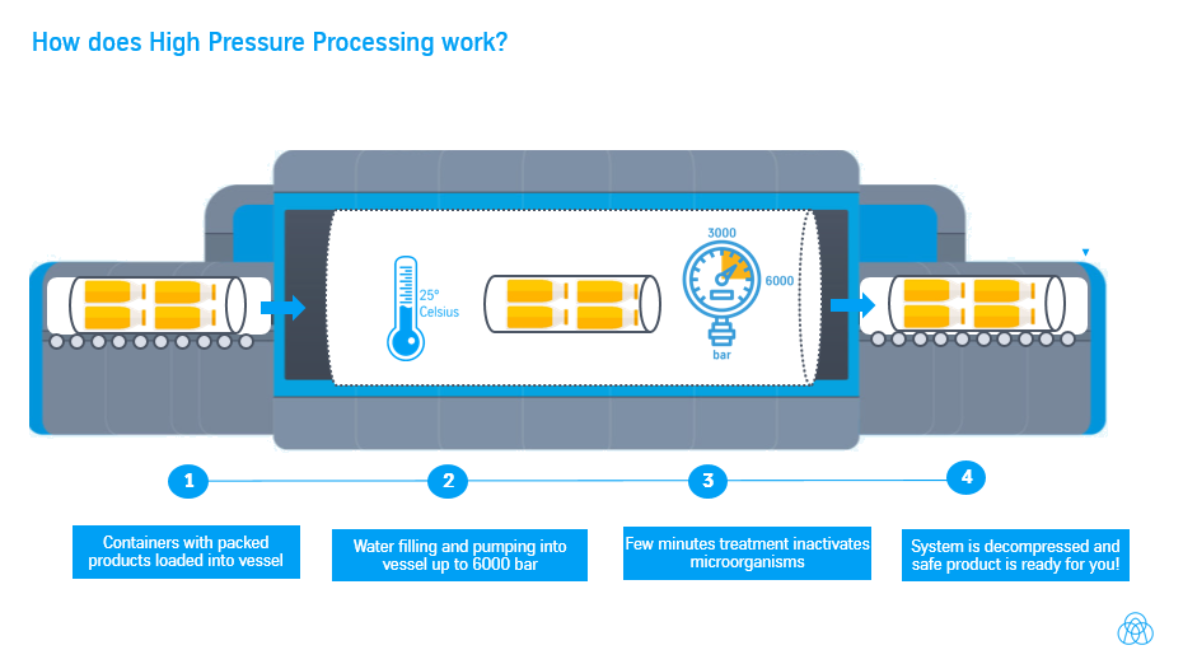

High-pressure processing is a batch operation. Typically, the product is packaged in a flexible container (a pouch or plastic bottle), and is then loaded into a sample basket. The sample basket is then loaded inside a high-pressure chamber filled with a pressure-transmitting fluid such as water. The pressure-transmitting fluid in the chamber is pressurized with a pump, and the pressure is transmitted through the package into the food. During pressurization, there is a transient temperature rise in foods (3 degrees Celsius/100 MPa) due to adiabatic heating. The product is pressurized, and held under pressure for a specific time, usually 2–5 minutes, before being depressurized. The product temperature then returns close to its initial value. The processed product is then removed and stored or distributed under refrigerated conditions.

Most foods are thermally processed to kill spoilage or pathogenic bacteria, which often diminishes product quality. High-pressure processing (HPP) provides an alternative means of killing bacteria by using pressure as the lethal agent. HPP conducted at refrigerated (or ambient) temperatures prevents thermally induced off-flavors and retains quality attributes, especially in heat-sensitive products. Pressure treatments can eliminate or reduce the need for synthetic additives in product formulation. This helps the food processors to satisfy consumer demand for clean-label products. During HPP, the treated products receive minimal or reduced thermal exposure. This helps retain the natural characteristics of the foods’ appearance, texture, and maintains enzymes and retains all nutrition.

Like heat, high-pressure treatment is a versatile pasteurization method for a variety of value-added liquid, semi-solid, and solid foods. Deli meat, guacamole, seafood, ready-to-eat meals, sauces, juices and beverages, jams, salsa, pet foods, baby foods, fruits, and vegetables products are some representative product categories that are pressure treated. Acidic foods (pH < 4.6) are particularly good candidates for HPP technology.

Like any other processing method, HPP cannot be universally applied to all types of foods. Foods with entrapped air pockets such as breads, cakes, mousse, strawberries, and marshmallows are not suitable for HPP. These foods might be deformed under pressure due to the compressibility difference between air and food. In addition, foods with low-moisture content such as spices, powders, and dry fruits are also not suitable for HPP because the microbial lethality of pressure diminishes under low-water activity conditions.

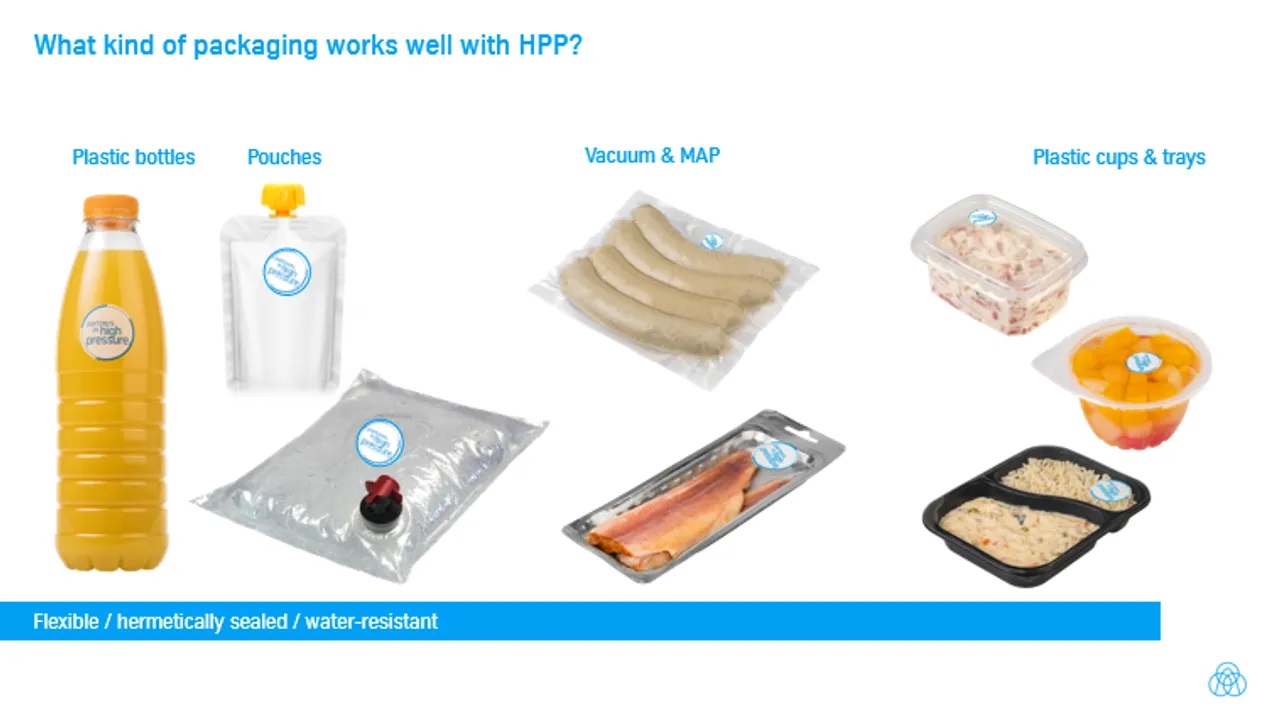

During pressure treatment, the food and packaging material may undergo a 15% volume reduction and then return to its original volume upon depressurization. This requires that the packaging be flexible enough to withstand a transient volume reduction while under pressure. HPP products are typically vacuum-packaged using flexible pouches or containers. Polyethylene terephthalate (PET), Polyethylene (PE), Polypropylene (PP), and Ethylene vinyl alcohol copolymer (EVOH) are the commonly used packaging materials. At least one interface of the package need to be flexible enough to transfer pressure. Rigid packaging containers such as glass bottles or tin cans cannot be used for HPP due to the inability to transmit pressure to the food product. The packaging material must also be able to survive intensive pressure treatment and needs to have high-barrier properties towards moisture and oxygen transmission.

The Hazard Analysis Critical Control Points (HACCP) regulations used by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recognize HPP as a pasteurization process to satisfy a 5-log reduction of pertinent pathogens in juices. Similarly, HPP is recognized by the FDA as a decontamination process for Vibrio bacteria in raw oysters and seafood. The United States Department of Agriculture Food Safety Inspection Service (USDA FSIS) recognized HPP as a post-lethality treatment for the control of Listeria monocytogenes in ready-to-eat (RTE) meat products. Health Canada, the European Commission, and other regulatory agencies have recognized HPP as a food pasteurization process. Food processors should, however, conduct appropriate validation studies. Since pressure-pasteurization treatment does not inactivate bacterial spores, pressure-pasteurized products should be distributed under refrigerated conditions.

High-pressure treatment modifies the cellular morphology of microorganisms and damages cell membranes, ribosomes, and enzymes, including those involved in DNA replication and transcriptions. An insufficient intensity of pressure treatment, however, may only injure a proportion of the bacterial population. The injured bacteria in HPP processed foods may then recover during storage time. Generally, gram-positive bacteria are more resistant to high pressure than gram-negative bacteria. This resistance may be attributed to their thicker cell walls. High pressure above 60,000 pounds per square inch inactivates most vegetative bacteria, but spores survive pressure treatment at ambient temperatures.

HPP treatment can extend the shelf life of food products up to 300+ days depending upon the choice of process parameters and product formulation. The product’s shelf-life extension is based on the parameters of the process (pressure, temperature, and holding time) and product (acidity, water activity, and composition). Choice of packaging materials must also be considered. In addition, the storage temperature used after HPP is another factor that can most influence the shelf life of the product- which mainly require refrigeration after HPP.

High-pressure pasteurization kills vegetative bacteria. On the other hand, pressure treatment at ambient temperatures does not inactivate bacterial spores. As a result, HPP products that are currently marketed worldwide need to be refrigerated during their distribution. In some cases, this is necessary for safety (to prevent the outgrowth and germination of spores in low-acid foods).

High-pressure pasteurization kills vegetative bacteria. On the other hand, pressure treatment at ambient temperatures does not inactivate bacterial spores. As a result, HPP products that are currently marketed worldwide need to be refrigerated during their distribution. In some cases, this is necessary for safety (to prevent the outgrowth and germination of spores in low-acid foods).HPP does not break the covalent bonds in foods and therefore has a limited effect when compared to thermal processes on low-molecular-weight compounds such as flavor compounds, vitamins, and pigments. As a result, the quality of HPP-treated food is similar to fresh food products, and their quality degradation is influenced more by their storage and distribution after processing. HPP also provides a unique opportunity to create new food textures in protein- or starch-based foods. In some cases, pressure can be used to form protein gels and increase product viscosity without using heat.

During HPP, pressure is uniformly applied around and throughout the food product. In contrast, imagine how a grape placed between fingers can be easily squeezed and broken. This is because the pressure is not applied evenly from all sides simultaneously. However, if this same grape is squeezed from all sides simultaneously, it will not be crushed. This can be demonstrated by placing a grape inside a container filled with water. By squeezing the container, the water inside as well as the grape is pressurized. Yet the grape is not damaged even with hard squeezing. Similarly, foods processed by high pressure are not damaged.